There have been comedians grappling with darkness since there have been comedians. We see these archetypes in Shakespearian fools and motifs of the sad clown just as often as we see them on stages in front of brick walls. However, no performer plays with form and layers of reality like Bo Burnham, who at times seems to be a walking retaliation against the very idea of putting art into boxes. Burnham’s performances are a combination of stand-up comedy, music (accompanying himself on the piano, guitar, or pre-recorded track), poetry, and lectures, and that’s only covering the breadth of his forms, for his content includes everything from dick jokes to existential dread and back again, often in the same song. Yet despite all this outward unconventionality, Bo Burnham’s three specials carry an implicit arc that is worthy of Aristotle’s Ancient Greek stage. Despite being a comedian by name, using Aristotle’s own rules Bo Burnham might very well be the best example of a modern tragic hero.

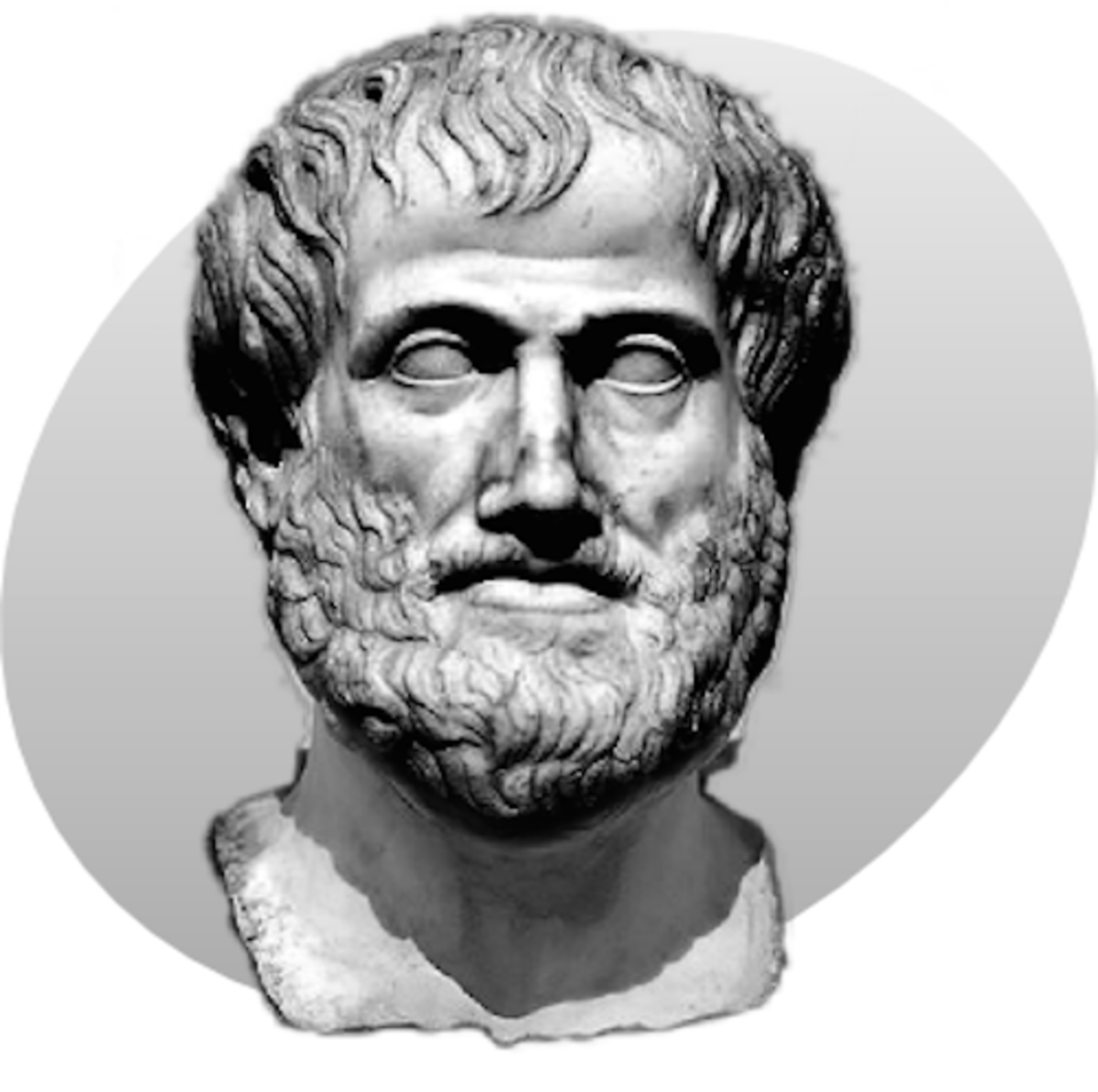

A professor once explained to me that she believes Romeo and Juliet is a comedy and not a tragedy. There is no grand hubris or epic flaw that brings about the young lovers’ downfall, simply a sitcom-esque mix-up from the hands of the nurse and the friar. Tragedy, like all art, is determined by the people who are paying attention. Scholars make the rules, and those rules exist until other scholars come along with better ones. My favorite thing about art, after all, is its eternal arguability. Whether you agree or not, this claim about the invalidity of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedy is a reminder that more than tone and resolution is important when determining what constitutes a comedy, tragedy, or something else entirely. The oldest and most famous set of guidelines for tragedy is Aristotle’s Poetics, written in the 4th century BCE, which included a definition of tragedy as well as its six necessary elements: plot, character, thought, diction, song (or melody), and spectacle.

In the two and a half millennia since Aristotle’s time, art has evolved and outgrown a great deal of his principles. For example, he believed “If an artist were to daub his canvas with the most beautiful colours laid on at random, he would not give the same pleasure as he would by drawing a recognizable portrait in black and white.” This is a sentiment proved obsolete by much of the major art movements from the last hundred years. In a similar fashion, the clear lines between comedy and tragedy have faded as well, but nowhere do we see the two mingling as potently and as frequently as in stand-up comedy. Edith Hall, a professor of Classics at King’s College in London, once remarked that “More than any other art form I’ve had experience of, Greek tragedy does one particular thing and that is look suffering and human misery directly in the face.” I believe that an hour in a local comedy open-mic may change her mind.

Bo Burnham began his career nine years ago at the age of 16. He uploaded a video onto Youtube, which at the time was less than two years old. His first few videos were of him singing self-deprecating comedy songs in his bedroom about things like being a nerd or people thinking he was gay. At the time, Youtube wasn’t yet a way to become famous, simply a way to share videos, or in his case, to share his new songs with his brother who was away at college. In many respects, Bo Burnham is second only to Justin Bieber for being an early “YouTube Sensation.” His videos began to gain some serious traction, and in 2008 he signed a four-album record deal with Comedy Central and released his first EP. Two years later he went to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival and won both the Panel prize for The Act Who Has Most Captured the Comedy Spirit of the 2010 Fringe and the Malcolm Hardee Act Most Likely to Make a Million Quid Award. Now at the age of 25, Bo Burnham has appeared in numerous films, created and starred in his own TV show, written a book of poetry, toured all over the world, and released three full-length comedy specials.

Throughout the course of his three specials, Words, Words Words (2010), what. (2013), and Make Happy (2016), Bo Burnham achieves each of the six requirements of a tragedy as defined by Aristotle: Plot, Character, Diction, Thought, Song, and Spectacle. The most obvious of these are the last two: song and spectacle, which Aristotle says “represent the media in which the action is represented.” His specials are peppered with poetry, speeches and other forms of expression, but songs are always at the heart of Bo’s performances. It is through song that the bulk of his ideas are conveyed. Burnham’s shows are full of spectacle, from the large-scale choreographed lighting in the finale of Make Happy to the small-scale confetti that sits in his pocket until he tells one particular joke near the end of what.

Diction, which Aristotle says involved the manner of the representation, is “the expressive use of words” which he goes on to say has the same force in both verse and in prose. Bo Burnham expresses himself through traditional and nontraditional uses of language. Traditional uses include an entire song entitled Irony with lyrics like, “A water park has burned to the ground,” and “I’m a stand-up comic and I always sit and slouch.” He quotes T.S. Eliot in his song Repeat Stuff and references Oedipus Rex in Words, Words, Words. He even wrote an entire Shakespearean sonnet for Words, Words, Words (whose title is a reference to Hamlet.) He even speaks to Shakespeare directly at one point, starting with, “I’ve got a bone to pick with you William, so if you could just listen up here and listen to this theater queer’s theater query here….” Burnham plays haikus (“For 15 cents a day you can feed an African. They eat pennies”), Shel Silverstein-style poems, and the traditional fairytale structure. He has a country song, a hip-hop song, numerous raps songs, and a few love ballads. He also strayed into the absurdist with a series of statistics in his material, including the ridiculous but not incorrect “The average person has one fallopian tube.”

The next three requirements are the ones pertaining to the matters of the story itself. Aristotle considered plot to be the most vital of these, being the essence of any dramatic work. Unlike traditional tragic heroes, Bo’s tragedy is all internal. No eyes get destroyed and no kingdoms are lost, but we get to watch as Bo tries to come to terms with his head and his heart. As per Aristotle’s rules, there are no moments of deus ex machina and no episodic plots, just a man on a journey. Throughout his three specials, Bo leaves breadcrumbs of a very tangible arc through anxiety, depression, dread, defeat, and supplication. If all a viewer is looking for, however, is silly jokes, then they will leave the show remembering the silly jokes. Burnham’s moments of introspection are all couched in brilliant artistry, but nonetheless are right there for those who are looking. Even the titles themselves can tell a part of the story. Words, Words, Words highlights the confusion and feeling of being swept up, what. speaks to the emptiness and dissociation he feels as he grapples with his success, while the final Make Happy hints at a critical emotional event and some semblance of a resolution.

Words, Words, Words, which came out when Bo was 19 years old, shows his first analytical look at stand-up comedy. It opens with songs entitled What’s Funny and Men and Women, as the young comedian is trying to unpack the form. In the same way that the first book Jane Austen wrote is a novel about novels, the first special Bo produced was a comedy about comedies. The first step in his tragic arc occurs in the song Art is Dead. Bo Burnham comes face to face with his own profession, and sings about his disillusionment with art in the 21st century: “I must be psychotic, I must be demented, to think that I’m worthy of all this attention... My drug’s attention, I am an addict, but I get paid to indulge in my habit, it’s all an illusion.” This song marks the first big departure from the light-hearted silliness that filled his early performances. Words, Words, Words marks our hero’s moment of catastrophe. While a catastrophe is often thought of as a great calamity, it can be more closely translated as a change of fortune or turning point. Despite what it seems, Bo Burnham’s sudden success at the time of this first special is his catastrophe in both definitions of the word, and seals his path into depression and existential dread.

The crack continues to widen three years later in what. The disillusionment intensifies as Burnham begins to question not only his art form but himself and his perception of himself. In a brilliant piece entitled Left Brain / Right Brain, Bo Burnham “splits his neurological functions” and performs a duet between the two sides of his personality. It begins with light humor as the two sides present themselves:

Left: “I am the left brain, I am the left brain, I work really hard ‘til my inevitable death brain. You got a job to do, you better do it right and the right way is with the left brain’s might.

Right: “I like oreos and pussy, yeah! And I cried for at least an hour after watching Toy Story 3. Woody! I am the right brain, I have feelings, I’m a little all over the place but I’m lustful, trustful, and I’m looking for somebody to love (or put my penis in.)”

This dialogue continues with the two sides arguing and beginning to fight with each other (Right: “At least I don’t still play with toys!” Left: “Rubik's cubes are not toys! They keep my spacial reasoning skills sharp!”) The piece continues to escalate and climaxes with the two sides of the brain fighting over who is at fault for Bo’s increasing depression. Left eventually makes Right cry by screaming, “Well at least I did my fucking job, alright! I kept him working, I kept him productive. You were supposed to look after him… if he’s feeling unhappy it’s because you failed him. You did this to him, he hates you I know he does, he fucking hates you!” The piece ends with Left suggesting that they perform comedy together (“You can man the themes, I’ll man the form...”) as a way to try and cope.

what. ends with a piece called We Think We Know You. The piece is experimental in form, and follows Bo making literal music out of the daily conversations that give him so much anxiety. Much of the piece is beyond written explaining, but it culminates with these phrases spoken by three characters all performed by Burnham: “We think you’ve changed, bro.” “We know best.” “You suck.” They are repeated over and over again until it simply becomes: “We think. We know. You. We think we know you. We think we know you.”

His third special, Make Happy, came out in 2016 with Bo Burnham at age 25. The show opens with a satirical song about how hard his life is, entitled Straight White Male (“I’ve never been the victim of a random search for drugs, but you can’t say my life is easy until you’ve walked a mile in my Uggs.”) This piece beautifully mirrors the reality of the live show’s finale, entitled Can’t Handle This. Can’t Handle This is the climax of Bo Burnham’s three-special story and the breaking point of his interior world. The song starts with a setup that he is going to be talking about his problems, and after a long instrumental he finally starts, saying, “I can’t fit my hand inside a Pringles can.” The audience explodes and he goes on to talk about Pringles cans, and in the next verse he complains about how when he went to Chipotle the burrito was too big and it wouldn’t all fit inside the tortilla (“I’m okay with small mistakes, if you’ve got no more chicken I’ll take pork, but I’ll blow my dad before I eat a burrito with a fork.”) The silliness continues until the lights and the music go down, and Burnham finally allows himself to have a frank moment with the audience. “I can sit here and pretend like my biggest problems are Pringle cans and burritos. The truth is, my biggest problem's you. I want to please you but I want to stay true to myself... Part of me loves you, Part of me hates you. Part of me needs you, part of me fears you, and I don't think that I can handle this right now.” Bo repeats “I don’t think that I can handle this right now,” over and over again, before remarking, “Look at them, they're just staring at me like ‘come and watch the skinny kid with a steadily declining mental health’ and laugh as he attempts to give you what he cannot give himself.” He continues with “Can’t handle this right now,” as the audience stares up at him, not sure what to think. As the song is coming to a close he says, “ I know I'm not a doctor, I'm a pussy, I put on a silly show. I should probably just shut up and do my job so here I go.” With this, he seamlessly goes back into the bit about Chipotle burritos and the audience starts laughing again in spite of themselves.

If you are at the live show, this is where the performance ends. However, if you are watching the special at home, Bo treats you to one more song. You hear the applause and watch as he walks backstage, sits down at the piano, and sings one more time. This song is free of any frills and provides the Aristotlean katharsis, which is often the most important aspect of a tragedy. It is the part that cleanses and purges the audience. The song is called, Are You Happy? He asks the listeners if they are happy, saying that “I’m open to suggestions.” The song and the special ends with him singing, “So if you know or ever knew how to be happy… on a scale from one to two now, are you happy? You’re everything you hated, are you happy? Hey, look Ma, I made it, are you happy?” This moment of supplication marks the finale of Bo Burnham’s tragic arc. The fear and pity that Aristotle wants a tragedy to invoke is laid at our feet. Well, sort of. The beauty of Bo Burnham’s particular catharsis is its selectivity and its mercy. If you were at the live show, you got to leave a comedy show laughing about Chipotle. I believe Burnham spares his audience because somewhere he knows that they don’t really want to see what is happening backstage. The last moment gets to be about burritos, and that’s okay.

Earlier in the special, Bo takes a few moments to talk a little bit about his story. He describes what it has been like being a performer all his life. Like all great soliliquies, Burnham embraces authenticity and tries to level with his fans and with himself. He tells them, “I had a privileged life, and I got lucky, and I’m unhappy.” This moment of vulnerability marks Bo’s anagnorisis, which is the moment of recognition within the tragic structure. It emphasizes how lost he is within a world he doesn’t understand anymore. As he says about himself in the opening of what: “He’s isolated himself for the last five years in pursuit of comedy and in doing so has lost touch with reality. You’re an asshole, Bo.” Bo has lost himself, and as the moment of anagnorisis emphasizes, it could very well be too late.

The second to last requirement for an Aristolean tragedy is all about character. Aristotle provides a checklist of attributes for our tragic hero. He needs to be renowned and prosperous, something easily verified by Burnham’s droves of fans and 180,000,000+ views on YouTube. He is good and his intelligence and skill level is worthy of his success. Burnham is constistent in his views, and frankly as consistent as anyone can be between the ages of 16 and 25. His journey evokes a clear fear and pity in the audience as they follow him on his journey, and what happens to him is not only neccessary and probable but remarkably unavoidable and a source for dramatic irony within his narrative.

This brings us to the thought of the tragedy, which can often be considered as a moral or greater concept. The impact of Bo’s story is that he gets what we all think we want, and he is so true to life that his humanity is his own downfall. In many ways, his tragic flaw or hamartia is hubris only in the sense that he hoped for a fulfuilling or happy life within show business and an imperfect world.

Like Oedipus’ relentless search for the truth, Bo Burnham’s tragedy is in a futile search for happiness in his tangled world. Neither hero’s flaw is simple, and both rely on unfortunate paths that looked so beautiful and shiny at the time. It isn’t that either character was tricked, it’s that the cards were stacked against them. They both chased good things, truth and happiness, respectively, and both seemed to be to their detriment. Towards the end of Make Happy, Bo tells his audience “I know very little about anything, but what I do know is that if you can live your life without an audience you should do it.”

I cannot be sure of what Bo Burnham is doing currently, but rumors have circulated that his is taking time off from performing, if not quitting entirely. His work will be severly missed by those who love him, yet his fans must understand the cost at which that work is produced. (The Shining and Shelley Duvalle) My favorite thing about Bo Burnham has always been his breadth of territory when it comes to content and tone. I watched Make Happy with two friends, and at the credits one was still giggling about burritos while the other was nearly crying. Bo Burnham is an artist that defies categorization and on the surface appears as a complete antithesis to Aristotelian thinking. Yet in all of his groundbreaking and all of his intertexuality, his story is able to fit exactly into one of the neatest boxes there is: that of the tragic hero. I’m not sure if this speaks to the wisdom of a great mind over 2,000 years ago or instead to how little things change when it comes to the fragility of human happiness. What I am sure of, however, is that a comedian as a tragic hero proves that Aristotle had no idea what was in store for mankind when it came to artistic expression and truth.